You are here

Home ›200 Years On: Engels and his Revolutionary Contribution

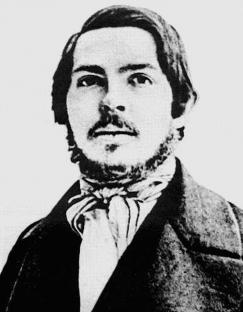

Today marks 200 years since the birth of Friedrich Engels. For this occasion we reproduce an article from Revolutionary Perspectives 1 (Series 3), originally published back in 1995 for the 100th anniversary of Engels’ death. It’s not a “celebration” or potted biography, it’s an attempt to evaluate his contribution to the development of Marxist method and the workers’ movement in the 19th century, and his continuing importance in the 125 years since his death. The arguments presented here in defence of Engels’ contribution, which also trace the origins of so-called “Anti-Engelsism”, remain relevant 25 years after they were written, as a new generation is once again attempting to exorcise Engels out of Marxism (see e.g. some of the communisateurs and value-form theorists).

The Indispensable Engels

Friedrich Engels, life-long friend and collaborator of Karl Marx, died on the 5th August 1895. It is 100 years since the working class lost one of its greatest fighters, and the co-founder of revolutionary communism.

Without Engels there would have been no Marxism, no Marxist movement. From the launching of the Communist League in 1847, to the founding of the International Workingmen's Association (the First International) in 1864, through to the setting up of the Second International in 1889 – to name but the most familiar political landmarks – the contribution of Engels was indispensable.

During periods of reflux, as in our own contemporary historical experience, it was Engels, despite separations from Marx and the dissolution of organisations, who placed himself at the centre of the struggle. It was he who maintained the vital work of the fraction through a mass of correspondence. After the death of Marx in 1883 it was Engels who lived and breathed the ''party spirit'', a continuity of organisational principles and experience transmitted right up to the Third International and thence to the historical present to the only tradition that embodies this political patrimony: the Communist Left.

Engels’ prosecution of the theoretical struggle, which in the "final analysis" cannot be separated from the political, stands as equal testimony to his stature. Over a century after their formulation, his ideas remain today a ferment of discussion and dissension. From a Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy in 1844, the work which opened Marx’s eyes to the fundamental nature of capitalist economy, to the co-authorship of the Communist Manifesto, from the early works jointly undertaken with Marx in response to the Young Hegelians, The Holy Family, The German Ideology, through to the works of his later years, Anti-Dühring, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, The Dialectics of Nature, from his material and intellectual assistance to Marx in the drafting of Capital to his numerous pamphlets and polemical pieces popularising the doctrines of revolutionary communism, Engels’ intellectual energies were tirelessly devoted to the emancipation of the proletariat.

This article is not a hagiography. We shall leave the armchair specialists of academic Marxism to pick over the bones of chronological data, etc. The "definitive biography" of Engels will only be written in the pages of the class struggle itself. We shall focus instead on a defence of Engels’ revolutionary Marxism, in an attempt to restore a reputation derogated by what has become an orthodoxy of professional defamation.

The Origins of 'Anti-Engelsism'

The emergence of a new undefeated generation of the proletariat during the reconstruction period after the Second World War, in the absence of the necessary subjective conditions for the political reconstitution of the class, saw the rise of various species of left radicalism. The early signs of crisis in the new accumulation cycle, the first cracks in the Cold War consensus, the growth of CND and the New Left, opposition to the Vietnam War – these were some of the conditions which radicalised new layers of the intelligentsia and inevitably at the same time generated a new interest in the ideas of Marxism.

This process led to a greater questioning of some of the more obvious inanities of reformism, and of the dead weight of the ideological monolith of Stalinism. Consequently critics began to search the writings of the founders of Marxism for the seeds of Stalinism and the failures of reformism, a process that fuelled the expansion of academic Marxism. This coincided with the wider availability of Marx’s early 'humanist' writings. A new consensus began to emerge about the nature of Engels' thought. That this was the outcome of a thorough-going idealist method – an issue space prevents us from further exploring here – did not mean that it was any less 'influential'.

The dominant tone of the period emphasised philosophical and cultural analysis often in reaction to the crude reductionism of Stalinism and the anti-theoretical bent of reformism. The marxicologists of the New Left however, proved congenitally incapable of superseding these phenomena. To presume that reductionism or pragmatism in theory led to, much less 'caused' Stalinism or reformism, is to pursue the blindfold of an idealist method tout court.

Once this logic was accepted it was not long before intellectual lines of inheritance are scoured to find the thinker who first introduced such erroneous ideas into the movement. The search for 'original sin' had begun.

The Critics

One of the first studies to systematically assert a cleavage between Marx's ideas and those of Engels was George Lichtheim's Marxism: An Historical and Critical Study (Routledge, 1961). Lichtheim insisted that in Marx's vision ''critical thought was validated by revolutionary action", but in Engels' scheme ''there now appeared a cast iron system of 'laws' from which the inevitability of socialism could be deduced with almost mathematical certainty."(1)

Engels was supposed to have broken with Marx when he argued that "historical evolution is an aspect of general (natural) evolution and basically subject to the same 'laws'". Marx had taken from Hegel the importance of self conscious activity in the making of history. In contrast, what really "fascinated Engels'' was "Hegel's determinism: his ability to make it appear that nature and history followed a pre-ordained course."(2)

Lichtheim's book rehearses many of the themes that were to become familiar in a series of works published over the next twenty years: that Engels replaced Marx's notion of conscious activity with an empiricist notion of science, that he mistakenly extended Marxism so that it covered the natural as well as the social world in a manner analogous to the scheme of Darwinian evolution; and that these deterministic and reductionist formulations inevitably led him, at the end of his life, to endorse a reformist political practice on the part of the German Social Democratic Party.

Lichtheim inaugurated what was to become a pronounced tendency characteristic of what was to become known as 'Western Marxism': anti-Engelsism. Alfred Schmidt's The Concept of Nature in Marx (1962), argued that:

where Engels passed beyond Marx's conception of the relation between nature and social history, he relapsed into a dogmatic metaphysic(3)

Schmidt believed that where Marx saw ideas formed in interaction with the material world, Engels saw only a crude reflection of the external world in the brains of human beings, a vulgar 'copy theory of consciousness’.

By 1969 Lucio Colletti could question almost in passing:

How far this distortion of Marx's thought by Kautsky and Plekhanov ... was already prepared, if only in embryo, in some aspects of Engels' work and how in general the search for the most general laws of development in nature and history made these attempts a preconstitution of the contamination with Hegelianism and Darwinism.(4)

He went on to argue that Engels' influence on leaders of the Second International was partly a result of the place given in Engels' work to philosophical-cosmological development i.e. the 'philosophy of nature', in other words the 'extension' of historical materialism into ''dialectical materialism''.

According to Colletti, "dialectical materialism'' is a crude misunderstanding of which Engels alone was guilty. Under the illusion that he was founding a superior form of materialism, Engels supposedly reproduced, in a banalised form, the 'dialectic of matter', already present in its entirety in Hegel – quite unaware of the anti-materialist function that Hegel had explicitly assigned to it.

From Engels there supposedly sprang a pseudo-Marxist tradition encompassing all of Marxism. The Lenin of Materialism and Empirio-Criticism who in the first part of Marxism and Hegel (1958), was still partially exonerated, by the second part (1968), was fully implicated in the indictment. So-called Western Marxism, from Korsch and the early Lukács down to Marcuse, despite its anti-materialist and anti-Engels polemic, also supposedly betrays its line of descent from Engels' fallacious Marxism.

By the early 70's the pattern was fully established – Engels was the villain. It did not seem to matter what political or theoretical position a writer set out from – the neo-Kantianism of Colletti, the humanism of Schmidt, the Althusserianism of New Left Review – the destination was always the same: Engels was the root of whatever was wrong with Marxism. A flood of publications by Levine, Carver, Coulter, Jordan, Gunn, et al., to name but a few, saw this tendency congeal into a virtual orthodoxy.

The Unity of Thought of Marx and Engels

The standpoint that there was a fundamental cleavage in the thought of Marx and Engels ignores the palpable reality, the recorded evidence of a lifelong partnership. Overcoming the elementary biographical facts of the two most famous lives in the history of the communist movement requires considerable distortion. Only the crudest methods of idealism could encompass such a feat: only a pre-conceived end can pervert the empirical data in order to sustain such a fixed idea.

For Carver: "the intellectual relationship between the two living men, was very much the story of what they accomplished independently". After Marx's death "Engels moved into an all powerful role", in which he ''invented dialectics and reconstructed Marx's life and works accordingly".(5) Levine even more strikingly demonstrates the reactionary logic of the idealist method when he poses the question of:

why basic intellectual differences between the two men did not come to the surface as tangible and real, articulated and acknowledged dispute.(6)

The idea that Marx and Engels developed along separate theoretical paths finds no support in the biographical evidence. A cursory glance at the latter bears this out.

In the 1840's both men arrived at what was to become known as the historical materialist view of the world, and in several important instances it was Engels who led the way. The entire content of the joint work, the Communist Manifesto, was first outlined by Engels in Principles of Communism. Marx was still extracting himself from the coils of Hegelian philosophy when Engels wrote his Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy. This was to provide the crucial impetus for Marx's 40 year immersion in economic analyses, and was also the immediate inspiration for Marx's transition to a fully materialist class analysis, a process recorded in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844.

Having arrived at a common outlook, Marx and Engels co-authored two key works which elaborated their views, The Holy Family and The German Ideology. They struggled together to win the organisation they were both involved in, the League of the Just, to their ideas, transforming it into the Communist League. In 1848 a series of bourgeois revolutions broke out across Europe. Marx and Engels actively took part, in order to contribute to the emergence of conditions which would promote the political and economic development of the proletariat.

The start of Marx's exile in England and Engels' life in Manchester inevitably altered the pattern of their joint work, establishing a new political and intellectual division of labour between them. In the long gestation of Capital, Engels was Marx's constant adviser, either in their almost daily exchange of letters or in discussion during visits. Constant collaboration continued at every stage of the writing of Capital up to and including the reading of the proofs which Marx largely entrusted to Engels. Marx insisted ''your satisfaction up to now is more important to me than anything the rest of the world may say of it". At the end of it we are left in no doubt as to the nature of his debt to Engels:

Without you I would never have been able to bring the work to completion, and I assure you, it has always weighed on my conscience like an Alp that you have dissipated your splendid energy and let it rust on commercial matters, principally on my account, and into the bargain, still had to participate vicariously in all my minor troubles.(7)

Levine argues that Marx's death left Engels free to "publish his distorted version of Marxism". But even the chronology of publication which Levine gives undermines his own argument. Anti-Dühring was not only published during Marx's lifetime, the whole project was Marx's idea, Marx himself writing one of the chapters for it. Are we to understand that Marx is supposed to have been a witness to the decimation of his philosophy by his closest friend without batting an eyelash, that he apparently never felt the need to dissociate himself from a 'metaphysical construction' that was the 'antithesis, of his own thought!

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific was extracted from Anti-Dühring and also published before Marx's death. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State appeared after Marx's death, but was composed by Engels using ethnographical notebooks Marx himself had written. Ludwig Feuerbach was published after Marx's death, but as if to stress the continuity of its ideas with the views of their early writings, Engels published Marx's newly discovered Theses on Feuerbach as an appendix. Obviously he saw no contradiction between the 'humanist' young Marx and the 'determinist' older Engels.

An extract from a letter by Paul Lafargue, husband of Laura Marx, perhaps conveys better than any historical retrospect, the true tenor and substance of their unique relationship:

Engels was, so to speak, a member of the Marx family. Marx's daughters called him their second father. He was Marx's alter ego … From their youth they developed together and parallel to each other, lived in intimate fellowship of ideas and feelings and shared the same revolutionary agitation ... But after the defeat of the 1848 revolution, Engels had to go to Manchester, while Marx was to remain in London. Even so, they continued their common intellectual life by writing to each other almost daily … As soon as Engels was able to free himself from his work he hurried from Manchester to London, where he set up home only ten minutes away from his dear Marx. From 1870 to the death of his friend, not a day went by but the two men saw each other, sometimes at one's house, sometimes at the other's … Marx appreciated Engels' opinion more than anybody else's, for Engels was the man he considered capable of being his collaborator, for him Engels was his whole audience. No effort could have been too great for Marx to convince Engels and win him over to his idea. For instance I have seen him read whole volumes over and over to find the fact he needed to change Engels' opinion on some secondary point ... It was a triumph for Marx to bring Engels round to his opinion. Marx was proud of Engels. He took pleasure in enumerating to me all his moral and intellectual qualities ... He admired the versatility of his knowledge and was alarmed that the slightest thing should befall him.(8)

Vulgar Critique of a "Vulgar Materialist"

Colletti, like Schmidt and Fetscher(9), maintains that Engels ventured into a useless and negative operation when, under the spell of the very vulgar materialism he sought to oppose, he attempted to enlarge Marx's historical materialism into 'cosmic' dimensions. Briefly, the argument is as follows: Marx's great achievement, at once gnoseological(10) and socio-political, was to have understood that through their labour human beings enter into social relationships with nature. Consequently there is no knowledge that is not a function of humanity's transformation of nature. Having attained this revolutionary insight, superior in object, method and idea to all previous philosophy, why should one regress back to a philosophy of nature in itself'?

A closer look, however, reveals that such an opinion is misconceived both theoretically and historically. It fails to take proper account of the changed philosophic-scientific setting in post 1850 Europe, compared to the era in which the young Marx formulated his criticisms of Feuerbach. Although a Moleschott or a Buchner was inferior to a Feuerbach from a purely philosophic standpoint, nevertheless their materialism had many more links to the natural sciences than had Feuerbach' s essentially naturalistic humanism.

The former were not satisfied merely with asserting the primacy of the sensuous over the conceptual or with turning theology into anthropology. They were to search for an explanation of sensuousness – as well as intelligence and morality – in biological terms. The objection raised by Marx against Feuerbach, that the latter overlooked the 'active side' was still valid, but it appeared insufficient and over general, since the claim of the new materialism (as well as of 18th century French materialism) was to explain even this active side in scientific terms i.e. as a complex of 'material' processes obeying certain laws.

It is important to acknowledge that the claim was correct, even if the subsequent execution of the plan was simplistic and crude. These crudities were the result primarily of two factors: 1) the reduction of human cultural, moral and political behaviour to biological activities without any mediation, and thus a failure to take account of the 'second nature' which labour confers on human beings within the animal realm, to which they still continue to belong; 2) the understanding of social inequalities and injustices as 'ills' to be cured by science, and thus a thoroughgoing failure to recognise the necessity of class struggle and thence an omission of any analysis of the class position of scientists themselves and how this conditions their theoretical output.

A reply to these one-sided intellectual developments should have been given within the framework of materialism and not merely as a revindication of the subjective element. This became all the more important after Darwin's great discovery gave rise to a second wave of materialism, which overtook the old conception of nature as an 'eternal cycle' (e.g. still shared by Moleschott(11)) and which demonstrated that historicity was not a characteristic peculiar to humanity.

Among other things, evolutionism posed again the question of the existence of nature before humanity, of the origin of humankind and its future disappearance. To what extent would the 'second nature' established with the appearance of labour and what might be called a 'third nature' developed with the advent of communism, be able to push back the biological limits of humankind? These were questions raised by a philosophy which, however crude and reactionary it may have been in other respects, threw new light on the objective reality of humanity's situation as revealed by scientific research. This in itself was a powerful antidote to anthropocentrism.

Contemporaneous with this current of thought in the middle and late 19th century, was that of a degenerated empiricism, which tended towards agnosticism but was not above flirting with religion. What was to become the 'reaction against positivism', an idealist renaissance that flourished with the onset of decadence at the beginning of the 20th century was already germinating within positivism itself.(12)

It was within this complex situation that the so-called cosmological development of Marxism took place. However, it is important to state that this did not represent an impulsive direction undertaken by Engels, but rather an objective politico-theoretical necessity. Any serious examination of the differences between the two founders of Marxism would require to begin not with facile contrasts between the philosophic profundity of the one and the alleged superficiality of the other, but rather on the division of labour established between them, itself a product of limits imposed by their specific historical situation. It was Engels, during this period, who took on the tasks of polemicising with contemporary culture, while Marx concentrated all of his energies on a single great opus, Capital.

To regard Engels’ writings on the natural sciences as merely a banalised repetition of Hegel' s philosophy of nature, or as a partial capitulation to vulgar materialism, is to overlook a fundamental feature of these writings: the polemic against the negative aspects of positivism. These negative qualities had on the one hand tended to become ''an empiricism which as far as possible forbids thought" and on the other, the claim of German vulgar materialism to "apply the nature theory to society and to reform socialism".(13) It is too simplistic to say that Engels rejected, in the name of the Hegelian dialectic, 'real materialism' i.e. the modern science of the day, as a form of metaphysics.

It is true that the Hegelian dialectic – even 'turned on its head' or 'extracted from its mystical shell' – was an inappropriate instrument for correcting the shortcomings of either vulgar materialism or agnostic empiricism, as Colletti has indicated. However it is mistaken to present this rejection of the Hegelian dialectic in terms of counter-posing a Marx who used it in a singularly valid way in the human sciences to an Engels who was so misdirected as to apply it to the natural sciences.

In relation to Hegel, both Marx and Engels were in fundamental agreement. Both were convinced that a materialist re-interpretation of the dialectic would require 1) that it be treated as a law or body of laws that have an objective existence – and not as laws of thought in relation to which objective reality is only a phenomenal projection; 2) that the existence of these laws in reality be established through empirical means, without doing violence to reality in order to make it agree with pre-established laws. The difficulty for them – as for us today – lay in the detailed execution of the second task.

If the use of the dialectic appears more sharply delineated, e.g. on "the negation of the negation", than in any of Marx's texts, this can perhaps be explained by the fact that the use of logical procedures originating within the historico-human sciences created greater problems when applied to the natural sciences. In so far as the natural sciences were, and still are, more advanced along the path of scientific precision, the unsatisfactory character of statements not formulated in quantitative terms is sharpened. It should be noted in passing that Marx himself was not at all hostile to the idea of a dialectics of nature. It is a well known fact that he gave a small example of it in a note to the chapter on the 'Rate and Amount of Surplus Value' in Book 1 of Capital; and in a letter to Engels he stated he was convinced that:

Hegel's discovery – the law of merely quantitative changes turning into qualitative changes – holds good alike in history and natural science.

A statement such as this rules out the possibility that Marx was only engaged in a 'flirtation' with the dialectic or are we to assume, as the anti-Engels camp maintain, that Marx allowed himself to be 'led astray by Engels'?

Engels and Reformism

A common accusation is that Engels' 'mechanical materialism' resulted in a reformist strategy which increasingly came to dominate the German SPD and the Second International of which it was a part. If socialism is 'inevitable', why endanger its progress by revolutionary adventures; why not wait for its inevitable progress to register in parliamentary majorities? These were formulations typical of what became known as 'revisionism' and are directly affiliated to theories of Engels' rigid and sclerotic objectivism. That they have any connection to the thought or overall political perspectives of Engels, is the result of selective quotation and distortion.

The seeds of this insinuation can in fact be traced to an argument first raised by Marx in a speech he gave in Amsterdam following the Hague conference of the First International where he said it might be possible, in England for instance, that ''workers can achieve their goals through peaceful means''. The weight of interpretation given to this quote is premised on a wilful neglect of Marx's general analyses of the Paris Commune, where he insisted that workers must ''smash the state machine'' and inaugurate the "dictatorship of the proletariat''. Later, in a similar vein, detractors latched on to Engels' preface to the first English translation of Capital, where Engels returned to Marx's remark that:

in Europe at least, England is the only country where the inevitable social revolution might be effected by peaceful and legal means.

However Engels goes on to add a crucial qualification:

He (Marx) certainly never forgot to add that he hardly expected the English ruling classes to submit without a 'pro-slavery rebellion' to the peaceful and legal revolution.

The full meaning of Engels' statement is therefore that, even if the working class in England were to attain power peacefully, they would then have to defend it by means of a revolutionary civil war.

Is it possible that the rise of revisionism was abetted by Engels' famous introduction to The Class Struggles in France, in which he expressed, shortly before his death, a pessimistic judgement on the possibility of armed insurrection in the cities, and ascribed a positive value to the electoral victories of the German Social Democratic Party?

The important point here – and one conveniently omitted by those intent on implicating Engels in the sins of revisionism – is that Engels' Introduction had to be censored at various crucial points in order to meet with the approval of the German Social-Democratic leaders. Engels regarded these passages as essential to his argument as can be seen in his letter to Lafargue on 3rd April 1895:

... Liebknecht has just played me a fine trick. He has taken from my introduction to Marx's articles on France 1848-50 everything that could serve his purpose in support of peaceful and anti-violent tactics at any price ... But I preach those tactics only for the Germany of today and even then with many reservations.

And elsewhere in similar vein in a bitter letter of protest to Kautsky, then editor of the SPD paper, Neue Zeit.

To my astonishment I see today in Vorwarts an extract from my Introduction, printed without my knowledge and trimmed in such a way as to make me appear a peace-loving worshipper of legality at any price. So much the better that the whole thing is to appear now in Neue Zeit so that this disgraceful impression will be wiped out.

Contrary then to the allegations, the Introduction does not at all assign to the proletariat the goal of a peaceful conquest of power by electoral means. Rather, the objective is the growth of the party under legal circumstances, so that it is then able to confront from a position of strength the inevitable final showdown, which comes when the bourgeoisie itself abandons the field of peaceful compromise.

Conditions of Theoretical Production

The process whereby knowledge is formed depends on the conditions of production of scientific conceptions and ideas in general. These conditions in turn are linked to the general conditions of production. The mode of production not only applies practically what science elaborates theoretically: it also has a great influence on the manner in which ideas and sciences are elaborated. Just as the capitalist division of labour imposes an extreme specialisation in all areas concerned with production, it also imposes an extreme specialisation, a further division of labour, in the area of the formation of ideas, and especially in the area of science.

The ruling class is capable of making a synthesis in the field of science as long as it doesn't have a direct effect on its mode of exploitation. As soon as it touches on this, it unconsciously distorts reality. In the spheres of history, economics, sociology, in the 'human sciences' in general, it can only arrive at an incomplete synthesis. When concentrating on practical application and scientific investigation it is essentially materialist. However any attempt at a total synthesis – since it is impelled for reasons unknown to it, to hide its own existence – results in the ideology of philosophical idealism.

Only the scientific socialists, beginning with Marx, were able to make a synthesis of the sciences in relation to human social development. This synthesis was in fact the necessary point of departure for their revolutionary critique. The development of knowledge in the workers' movement thus involves seeing the theoretical development of the sciences as its own acquisition, the starting point and motive for Engels' confrontation with ‘the philosophy of nature’.

Engels, like Lenin in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, had to deal with matters in which he was no specialist. Moreover, after Marx's death, he could do this only during the odd moments left him by the immense work of editing and publishing Capital and by the even larger political and organisational tasks that confronted him. The preface to the second edition of Anti-Dühring shows that he was aware of the risks and the fact that he failed to complete The Dialectics of Nature confirms this. Nevertheless it was impossible to avoid confronting the natural sciences and the philosophies that emerged from them. Whether either Engels or Lenin committed this or that theoretical error, whether on occasion they were over-schematic or lapsed into philosophical positions analogous to the bourgeois materialists of the past, is not the essential criterion on which they should be judged; it is rather, in their general activity, on their political orientation in relation to the prosecution of the class struggle. The real point is to understand how and why they situated themselves on the terrain of praxis of Marx's Theses on Feuerbach.

An attempt to integrate scientific developments into a more overall understanding centred around the practical realisation of the social revolution, the basis for all real progress; this was the motivating principle of the praxis of Engels and Lenin.

The workers' movement is identified by its particular revolutionary existence within capitalism, i.e. through its struggle. Consequently the development of its knowledge has a dual aspect, dependent on progress made towards real liberation of the proletariat. On the one hand it is political, involved with immediate and burning issues. On the other it is theoretical and scientific, evolving more slowly and, up until now mainly in periods of reflux in the history of class struggle.

Thus differences about political work are posed first in programmes, then in practical application, in day-to-day activity. The evolution of these differences reflects the general evolution of society, the evolution of classes, their methods of struggle, their ideologies, theories and political practice.

In contrast to this, the scientific dialectic in the purely philosophical sphere doesn't develop in the immediate way of the practical, political class struggle. Its dialectic is much more removed, intermittent, without apparent links either to local or wider social milieu – not unlike, for example the development of the natural sciences at the end of feudalism and the beginning of capitalism.

The more the sphere of knowledge is immediately connected to practical application, the easier it is to mark its progress. On the other hand, the more one is dealing with attempts at a wider synthesis the harder it is to elucidate the dialectic, because such a synthesis depends on laws of such a complexity and deriving from so many diverse factors, that it is practically impossible for us today to realistically tackle such studies.

This essay is merely a contribution towards clearing the ground for such efforts.

A large part of the resurrection of the Communist Left tradition in the UK has necessarily devolved around the spadework of political archaeology and the re-articulation of the fundaments of Marxist economic theory. In the face of the longest counter-revolution in the history of the workers' movement, where the voice of Marxism was all but extinguished, this has been an indispensable task consuming the best energies of comrades over a period of two decades.

Within the context of these pressing practical-political requirements it has been impossible for us to address other issues. Given that the leitmotif of most of 20th century 'Western Marxism' has revolved around philosophical and cultural analyses, we hope to be able to turn our attention to some of the questions raised therein in the forthcoming pages of this journal.

Anti-Engelsism, we have contended, is essentially a peculiar species of idealism. It can be traced to a neo-idealist renaissance that began to emerge towards the beginning of the century, a shift that involved an increasingly radical anti-objectivism. Although its point of departure were real and serious problems in the epistemology of the sciences, in the contingent historical context in which this crisis arose, this was used to reassert a mythological freedom and creativity of 'man', a new subjectivism-voluntarism, that ignored the real conditioning to which actual human beings were subject.

Although Engels offers us no ready made solutions to any of these complicated problems, as in so many important ways he was the point of our origin politically, in the confrontation of these theoretical questions, he is the point of our departure.

A.S.

Notes

(1) Lichtheim, p.238

(2) ibid., p.253

(3) Schmidt, p.55

(4) ibid.

(5) From Rousseau to Lenin, p.26

(6) Carver, Marx and Engels: The Intellectual Relationship

(7) Levine, The Tragic Deception: Marx contra Engels

(8) Marx and Engels: Selected Correspondence

(9) Irving Fetscher, Marx and Marxism

(10) i.e. as a contribution to the philosophy of knowledge [Ed]

(11) Moleschott (1822-93): German physiologist and philosopher who interspersed materialism and Hegelian idealism.

(12) Sebastiano Timpanaro, On Materialism, NLB

(13) The Dialectics of Nature, p.153; p.85

Revolutionary Perspectives #1

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.